Richard Mills, Imaginary Pictures: “Things that were gimmicks a couple of years ago have become useful”

Richard Mills has worked at the forefront of new imaging technologies for years. He is now focusing his expertise on capture for augmented and virtual reality, and the applications seem endless.

.

“Things that were gimmicks a couple of years ago have become useful”

..

FEED: Can you first tell us about Imaginary Pictures?

Richard Mills: Imaginary was founded just over two and a half years ago. My business partner Kevin Zemrowsky and I came from a feature film and TV visual effects background. We thought the best way to find a niche in the market was to specialise in capture – capture of scenes, capture of images, including ordinary camerawork and cinematography, but adding an air of science and research to find new methods of doing things. The business is supported partly by production services and partly by consultancy. We do a lot of consultancy work. One of our biggest clients is Sky UK.

In the VFX world, we had been doing moving background plates in 360 and 180. Then VR came on the scene and it was an easy move into capturing 360 for that field. Then we took a little side turn to look at other ways of capture for the future, including creating assets for mixed reality, virtual reality and other applications. That included volumetric capture, motion capture and a variety of other things.

FEED: Have we turned a corner in terms of the practical utility of AR content?

Richard Mills: Yes, it’s quite an interesting time for very augmented and mixed reality at the moment. We’re starting to get the benefits of research that was done two or three years ago. It’s starting to come into mobile products, some of which are gimmicky like Pokemon Go, others of which are actually quite useful.

There are several things just on the cusp of becoming widespread which are going to be really exciting. If you combine geolocation from GPS and augmented reality it gives you a really good view of, say, reconstructions of what the past might have looked like or visualisations of what the future might look like in a certain place.

And for entertainment, there are going to be lots of practical applications as well. Anything that has both engagement and a use is actually quite promising. There are a number of shopping apps, like Ikea’s, where you can previsualise the product in your home, or see yourself wearing an outfit before purchasing it. There are car configurators, which are one of the first spin-offs from the Google Tango project – you can see what different cars look like parked in your drive. They’re slightly gimmicky but also useful.

Judging by the number of articles and papers coming out of academia, educators are trying to pin together in a stable format GPS information and augmented reality so students can visualise how a city might have looked 100 or 200 years ago. And I know most of the big architecture firms have a VR department for visualisation.

Half of their offerings are done in a headset, and the other half are done with a mobile phone. Clients can not only see what the whole site might look like but details of the site as well.

IMAGE: Pokemon Go introduced augmented reality to the everyday tech user. Will practical AR become everyday too?

.

“In the mobile and PC worlds Unity is probably ahead, but Unreal engine is being used quite effectively by the broadcast industry.”

.

FEED: Where are you seeing the most interesting developments in AR hardware? Are we going to move from phones to glasses?

Richard Mills: HoloLens through the last couple of years has been the

pre-eminent device. Magic Leap shows great promise, and no doubt the field will be filled with more entrants over the next couple of years. I think this mixed reality and augmented reality that the glasses provide offers a level of accessibility that VR, with its closed-off-from-the-world

style, doesn’t.

But because there are so many mobile phones, that’s still a good entry into the market. You know if you have a good AR app that’s useful or entertaining or both, and it also works with a mobile phone it will have some traction.

FEED: Does the mobile phone limit what the technology can accomplish?

Richard Mills: The technology in the phone is quite good. It will recognize what the foreground and background is. It’ll place the object in front of or behind real world objects, so you can take a selfie with it or take a picture of someone, and it can work out what the foreground and background is and place you and a virtual object in the appropriate places. These assets are fairly lightweight.

One nice example is the Google Star Wars AR stickers for Android which feature multiple characters. They all interact with each other and interact with the viewer as well. If you approach them, they will run away or tell you to back off. If you add all those enhancements and create a bit of realism, people do engage quite nicely

with it.

The IKEA app is great too. It works in dimly lit rooms. It will match the lighting to the scene. You can place furniture to see how it looks in your house. It’s got a pretty good measurement tool now too which you can measure the space with. All this is on the phone.

FEED: You said that Imaginary Pictures is focusing on capture. How is capture changing in creating AR content?

Richard Mills: One of the most interesting fields we’ve been involved in is volumetric capture where you take an actor and capture the performance. But this is not like motion capture where someone wears a suit that then animates CGI assets. This is the actual performance captured in 360, captured from all directions, which can then be inserted into an application.

We did consultancy a couple of years ago for a company called Factory 42. They built a VR app with Sir David Attenborough called Hold the World in which David is in London’s Natural History Museum sitting behind a desk. You can pick up a number of objects lying there and he’ll talk to you about them.

Imaginary did the initial consultancy to figure out which of Factory 42’s four potential vendors had a product that would work for the project. Eventually the volumetric capture was done by Microsoft up in Seattle.

Volumetric capture is very interesting, but it’s complex, it’s expensive and the resolution has to be chosen carefully to make sure it will work on certain platforms. Ideally you want to run it on something like the HTC Vive rather than a mobile device.

We’ve moved on now to more lightweight forms of capture that are less demanding on processing power to play them. Volumetric capture assets are quite heavy duty, so in some cases it’s better to have CGI constructs to provide a lower processing overhead. A combination of CGI assets and volumetric capture assets in the same space can work quite well.

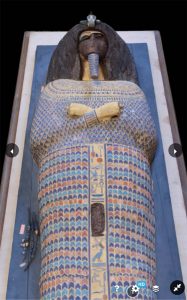

The other type of capture which works well for both AR and VR is scene capture. We did quite a lot of this in a project last year for Sky where we captured a number of tombs in the Valley Of The Kings in Egypt – Tutankhamen’s tomb and the tombs in Armana, plus about 20 artefacts and objects, ranging from Tutankhamen’s gold coffin to stones, tablets, and brooches. These were captured using photogrammetry, and then presented as objects for use either in AR or VR..

Richard Mills: Photogrammetry is constructing a scene from multiple photographic images. The photographs go into a modelling software which generates the geometry of the scene, and then clads it with the photographs.

You can produce a photo realistic rendition of a scene and realistic objects. These go particularly well with virtual reality. For instance, in the production for Sky, a number of tablets with hieroglyphs on them were captured. These went into a virtual reality production and you could interact with them, pick them up, look at them, turn them over, have the inscriptions on them translated for you.

A very useful technique.

FEED: What are the main platforms for delivering AR content?

Richard Mills: First, there are two main frameworks, Unity and Unreal, and most apps are built within these frameworks. There a couple of others as well but they’re mainly one of these two simply because a lot of work and development has gone into them. In the mobile and PC worlds Unity is probably ahead, but Unreal engine is being used quite effectively by the broadcast industry.

Nowadays, TV production, certainly sports coverage, will use a number of 3D assets. You can take player profiles in football, which are scanned assets of the footballers, and parade them up and down, animate them out into the frame and so forth. Years ago, they were just flat images on the screen.

Nowadays, TV production, certainly sports coverage, will use a number of 3D assets. You can take player profiles in football, which are scanned assets of the footballers, and parade them up and down, animate them out into the frame and so forth. Years ago, they were just flat images on the screen.

Most of that work is done in Unreal within the graphics engine, which is normally a Vizrt platform. We’re seeing Unreal doing a lot of that work in the broadcast field, but in the mobile and PC type apps, it’s mainly Unity.

But these are basically enabling technologies. They’re not a platform per se. The real competition comes between the various VR platforms. We’ve got the Oculus store. We’ve got Steam, and then there are a number of solo apps not related to either of the two major VR platforms.

So the actual method of disseminating content is really dependent on whether the publisher wants to retain control or if they want to have apps which can go on the Android Play or Apple Store or if they want purely stand-alone apps. I think one of the first stand-alone apps I saw was from Fiat which was for car sales and it was published independently, not on any platform. There is room for small developers to actually put stuff out there. It’s a bit competitive and independent, but you see some very, very useful things out there from small developers. It’s still useful to put an app on the stores because then you have got reach and can take advantage of recommendation and push, but if you were to avoid tying it to anything and make it, say, for a PC-based platform, there are a number of ways of doing that.

.. ..

..  ..

..

.

“We’re starting to get the benefits of research that was done two or three years ago”

.

.FEED: What does the future of VR, AR and 360 video look like?

Richard Mills: I think at the moment it’s a constantly changing world. Things that were gimmicks a couple of years ago have become useful, and that’s attracted the attention of the more serious players. So Sky, BBC, Discovery, Fox, Universal have all got VR apps and AR content as well. They see it as being important. Whereas a couple of years ago it was done for gimmicks or maybe an advertising stunt. People are now starting to monetise this.

There’s a rise in 360 video popularity. And with virtual reality the platforms are becoming more capable. In the next year, we’re going to see more mixed reality become available in bespoke see-through headsets or Magic Leap or other platforms that are coming out.

There are some serious players now looking at mixed reality to improve techniques within the workplace. Several car manufacturers are using Microsoft HoloLens for assembly training, assembly checking and for service and repair work. It enables you to have generalist trained service personnel rather than a specialist.

Another area there seems to be a bit of take-up is in medical applications. It’s quite possible now to be able to practice complicated surgical techniques in virtual reality before the operation takes place, and even during operation you can be coached by a remote expert to give extra input into an ongoing surgical process. I think this needs to be looked at carefully from the ethics point of view, but if it’s well curated and designed it definitely has a value.

Measuring up: A new generation of AR apps are practical tools for design, visualisation, medicine, study – and fun. The computing power and ubiquity of smart devices shows great potential for innovation.