Dr Florian Block, Digital Creativity Labs: “For us, esports is also an incredible space for experimentation”

Digital Creativity Labs at the University of York is a centre for studying the impact and possibilities of the rapidly growing genre of esports. Dr Florian Block leads the team and believes esports can unlock a whole new world of data analytics and content production

FEED: Can you first tell us a bit about your background?

Florian Block: My background is in HCI – human-computer interaction – which is concerned with creating and designing interactive experiences with users and for users, and optimising that relationship.

I went to Harvard and for five years worked on how we can use data to engage non-experts. Specifically, I worked on creating interactive visualisations for museums in which people could fly through large amounts of scientific data and learn about, in this instance, biology (Harvard’s Life On Earth project).

I’m very excited about data as a form of media that is for consumers, not just experts. That brought me, two and half years ago, to this post here at the Digital Creativity Labs at the University of York.

FEED: And what work is being done at York’s Digital Creativity Labs?

FB: We have an £18 million investment from various research councils, and our agenda is to deliver impactful research at the convergence of interactive media and games, and the rich space in-between. That, of course, includes broadcast, it includes storytelling. We’re mandated to work with industry. We want to enable the UK economy to be globally competitive and want to enable core technologies for that purpose.

Within the Digital Creativity Labs, I lead the esports research group. We have five full-time academics and research fellows and a couple of PhDs. We are a very interdisciplinary team, from data visualisation to human-computer interaction and user experience design, but also psychology and sociology. So we really look both at the tech and how the tech impacts.

We have staff who work on inferring the psychological traits of players by looking at their gameplay data. And we have students in machine learning and AI who analyse gameplay data to extract stories and insights for viewers and players.

FEED: How is the Lab’s work being used by the esports sector?

FB: Most of the data analytics in this space have focused on hardcore diagnosis and making pro teams and players better. Our key focus over the

past two and a half years – and it sort of makes us unique – is to translate esports data into meaningful stories for the audience.

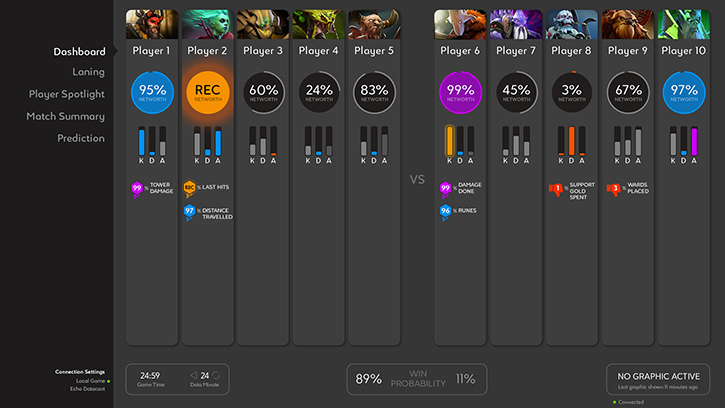

We look at complex data, extracting meaningful patterns or events or exotic, extraordinary moments, and then converting that data into a format that the creative team can use to make editorial decisions. So they could have access to three or four interesting things happening in a game that may have been overlooked by the commentators, and they can push this to the audience. Our system automatically translates these data patterns into easy-to-read content for the audience – things they can meaningfully interpret within ten seconds, because that’s how long you can interrupt their viewing experience. They could be things like: “This hero is better than 95% of previous players with that same character.”

It helps give people a context, because, bear in mind, the strategic space for some of these esports is super complex, and even veteran viewers, who also play a lot, cannot appreciate the performances of each individual hero. There may be ten players running around a virtual environment, and it’s very hard for audiences to track this fully.

FEED: And you have been working a lot with gaming network ESL.

FB: We’re really happy to be working with ESL and with the esports industry. It’s really been key to our mission. To do relevant work, it’s important to be working with the industry and the audience and the players. And we have a raft of products now. We do commercial work to some extent to fund further research at the lab.

We have products that can tap into the live performance data from an esports match and in real time compare it to historic matches. We have prediction technology that can give audiences a sense of who is leading or not. That’s not a trivial question in some of the complex esports. The numbers you see on-screen are not like a goal display you see in football. It’s much more complex than that. So we use prediction as a narrative element. And we look at products for the whole chain from analytics to authoring tools.

Companies like ESL want to create individual stories and convert that into something that adds value for the audience. It could create engagement for existing fans, but also potentially make esports more palatable for people who may be new to it. And with the rapid growth of esports, you are beginning to face a mainstream audience.

FEED: So you really are doing content creation, although it may not be via a linear, literary story.

FB: Yes. So far we’ve injected narrative elements on top of the game narrative. But we are currently exploring how to use the rich data space you have that surrounds a live game and historic matches, plus a viewer’s own matches and data. We are interested in going into hyper-personalised, interactive experiences.

On the viewer side, you may have the linear narrative that the commentator is giving – the one-for-all story – but you could also have a customised, tailored narrative that takes into account the viewer’s player data, with updates that say, “This player is doing better than your game by 10%”. So you get a hyper-personalised interactive experience that weaves through the main broadcast.

FEED: Can you tell me more about the different types of data you’re capturing? Are you collecting physical data about players, too?

FB: No physical data, although that would be interesting. We have toyed with heart rate monitors, but we’re mostly capturing the in-game data – the whole state of the game as it unfolds, how people move around the virtual environment, what actions they take. In a fantasy game, which spells they cast, what interactions they have with other players. Some games give you very good access, both in real time and retrospectively, about every little detail that happens in the matches.

You can compare this to tracking data in football and other traditional sports. But whereas you have to spend a lot of money for visual tracking technology in those, in esports you get all the tracking tech built in and innately pumping out data, so you have a much richer set of data to work with. More importantly, the sector is very permissive and companies are usually quite generous about sharing the data. As a result, you can get innovations that are unthinkable in football where you have to pay millions and can only get it if you are Sky Sports or the BBC. But everyone can get this data, so it’s a very exciting space.

FEED: Which games have you been working with?

FB: We’ve been working with DOTA 2 and Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. We’re starting to work with League Of Legends and Hearthstone.

FEED: Is there anything about these games that is particularly interesting from a data perspective? Or do you work with them because they are popular?

FB: It’s both. Yes, these are all very popular games. But DOTA has the most comprehensive free access to data. Valve, the publishers, are very permissive in their data use.

Hearthstone is a really interesting game in terms of vision technology. It’s easy to scan the video feed and look at what’s going on, because there are lots of static elements and lots of visual effects that make it easier to do image recognition.

What I would like to see in the next five years is an open data standard for games and behavioural data. After Cambridge Analytica, everyone has to be hyper-aware of the ethical implications of collecting behavioural data and using people’s content online. We want to be at the forefront of driving responsible data access.

Also, I think it is important that we democratise this data, so it’s not only research entities and large corporates that can mine this data for value – for instance, players could extract insights about strategies and performances from the data that help them be better players. If large game companies could agree on a common standard for gameplay data, we could work on easy-to-use tools to extract value from this data across games, and for the average esports fan. I think that would be a fantastic way of getting the games industry into a shared space in which everyone can innovate and be empowered based on human behavioural data.

FEED: What really is the difference between esports and real-world sports? People new to esports may think: “I’m just watching someone sitting in a chair.”

FB: First of all, esports really are a lot more complex. It’s not easy to watch if you don’t know the game. I guess that’s true for other sports, too, but the rules of football are easy to grasp just by viewing it. You have to bear in mind that these games were designed to be fun and competitive, they weren’t necessarily designed as an audience experience, but the community has made it into something that people watch.

Essentially it’s about skill. It’s about mental skill. It’s about strategy. It’s about understanding a tactical space and how to exploit weaknesses and leverage synergies between your teammates. It’s about reaction time. It has elements of physical performance, too. Some of these athletes do 200 actions per minute with a mouse and keyboard. It’s physically quite straining, which you wouldn’t expect.

And there’s the mental focus – some of these games are played over five hours for the best of five. There is a physical aspect similar to darts, and similarities to chess on a strategic level. I think that’s what many people don’t grasp, and that’s what attracts the audience.

Some of these people have incredible skill at playing these games. And some people are just really amazing in navigating these virtual tactical spaces. And I think that’s why people want to watch them. It’s the human performance that people want to see.

That’s very similar to sports; sports may be how athletic someone is in jumping and heading the ball. Whereas in esports you may react within a few milliseconds and you pull out just the right action to counter or prevent the enemy from killing you – it can almost be like rock paper scissors on steroids. It’s very intense and very fast paced in

many cases.

FEED: What applications for your research are there beyond entertainment? What other kinds of things are you learning?

FB: We have two motivations in working with games. First, games are in their own right an absolutely fascinating form of mainstream entertainment. And the UK economy is the fifth biggest in the world in terms of interactive entertainment. So the research we’re doing is important economically to enrich the audience experience and empower people to better understand what’s going on in the space.

But for us, esports is also an incredible space for experimentation. Because ultimately what we’re doing is looking at human behavioural data and translating that into a story that everyone can understand. And if I had to nail down a few challenges of the 21st century, the ability to make complex data and insights about us humans intelligible to mainstream audiences – not just experts – will be one of the really exciting, transformative areas. Using analytics – and also using artificial intelligence and machine learning – it’s going to be absolutely disruptive.

Esports today allows us to do research that we couldn’t do in physical sports and that we couldn’t do in many other parts of society. In esports, we have a tech-savvy audience of early adopters. They love technology, they love data, they’re eager to engage and they have an appetite. With esports, we can do something now that we probably won’t be able to for 20 years in other areas, but something that will definitely become relevant.

FEED: You study the interaction between humans and technology. In a wider sense, what is your take on how society is interacting with digital technology now?

FB: I think it’s obvious that digital technology and the way we share information is and has been evolving more rapidly than the culture broadly has adapted to. I think we’re really trailing the sorts of things that you can do with digital technology and communication. A lot of people see AI in particular as a danger in even further driving this gap between people and technology.

What we at the University of York and at DC Labs want to look at is how AI can be used to close that gap and to allow more people to judge large amounts of information. Whether that is how you can be better at esports or how you can judge whether a news article is authentic and genuine, it really is about giving people the opportunity to explore information more effectively, and using AI and data analytics to let people experience more information and make meaning from it.

I think we all have to try really hard to push to close this gap and to give everyone a chance to catch up.

This may sound idealistic, but I really think, from my experience in this research, there’s a lot that can be done.

I’m probably not as pessimistic as others – although the current political issues we have in this world are probably to a large extent caused by this gap between media literacy and the forces that manipulate the messaging. The more people we can enable to work with data, to become information and data literate, the more we can facilitate this. Through esports and games in general, but also through areas of science and learning, I think there’s some exciting stuff that’s going to happen in the next decade.

This article originally appeared in the August 2018 issue of FEED magazine.