Start-up: Videntifier, Iceland, 2007

With clients ranging from Facebook to Interpol, Videntifier is a visual search engine that incorporates computer processing and database technology to give computers the ability to recognise complex visual images. Founders Herwig Lejsek and Friðrik Ásmundsson developed the software over a decade ago, in collaboration with Reykjavík University and others.

Although the firm’s commercial progress was initially hampered by Iceland’s banking crisis in 2008, family and friends kept them afloat until a first deal was secured with the Icelandic police. This was followed by a contract with the UK’s Counter Terrorism Unit to help screen illegal and terrorist propaganda, to identify logos or known content. The speed and scale of the solution, which is capable of processing and identifying tens of thousands of hours of video per day, eventually led to bigger contracts. A tender for Interpol in 2012 was followed by a contract in the US for the National Centre for Exploited and Missing Children, while police forces from South Korea to Germany also use Videntifier software in their systems.

“In many European countries, there can be a significant misalignment between the published schedule of a TV show and its start time.”

While law enforcement became the prime use case, a cash injection in 2014 prompted them to look at other markets. One employee, who used to work for Icelandic telco Síminn, suggested media and telecoms, where the tech could be applied to copyrighting and EPG correction. “Not so much in the UK, but in many European countries, there can be a significant misalignment between the published schedule of a TV show and its start time, which is frustrating for the viewer,” explains Lejsek, who is now the firm’s chief executive.

Videntifier can separate assets and align TV streams with the EPG. The same technology can also be utilised to identify and differentiate between ads and content. This enables service providers to either facilitate binge watching by allowing users to instantly skip the ads, or they can do the opposite – enforce ads during the playback of catch-up TV and recorded content, or insert new ads programmatically based on the user’s individual profile.

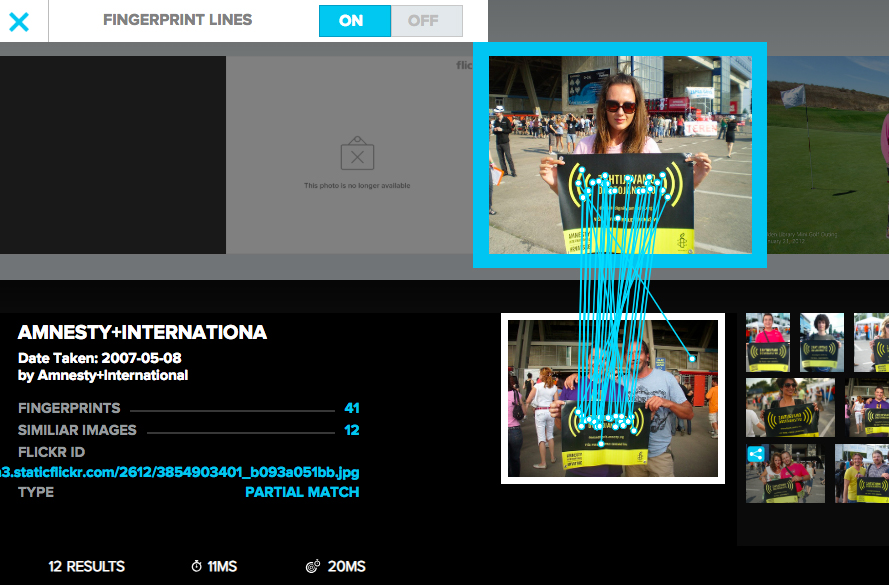

Stop and search: Videntifier is a visual search engine that can quickly and accurately identify videos and images

Another use case the company offers is copyright protection, comparing live web streams and video files to databases containing hundreds of thousands of hours of content or hundreds of live TV streams. Videntifier claims to be able to instantly identify a copyright violation without using watermarks and, according to Lejsek, has “extremely low false positive rates”.

“Our advantage is that we’re able to provide a very good visual comparison that’s also robust and we can do it to a large scale,” he says. “There are good fingerprinting technologies out there, and there are solutions that are fast, but not as robust. This is both, which has been proven in competitive tenders with companies in terms of accuracy and efficiency.”

Currently, its clients include Síminn, as well as Finnish firm Elisa and Eutelsat in France. Last year, the firm also licensed its technology to Facebook – which hired co-founder Ásmundsson, who has now left the company. As part of the deal, Videntifier is not allowed to say what the social media giant is using its technology for, although the firm’s main client base must furnish speculators with some clues.

While Facebook remains the firm’s only social media client, other social platforms might need some robust image recognition technology and copyright protection expertise once the EU’s overhaul on copyright rules kicks in. With the wording of Article 13 being finalised, the new rules are set to require the likes of YouTube to be liable for any copyrighted content and add harsher filters to any video uploaded.

Lejsek discloses that Videntifier is participating in the consultation process, but adds that it’s too early to call what kind of software is needed or how the directive will be implemented.

This article originally appeared in the April 2019 issue of FEED magazine.