Power struggle: How green is streaming video?

The streaming video ecosystem is less green than we all suppose. And it’s going to get worse very quickly.

Facebook’s 27,000-square-metre data centre in Lulea is powered by hydro electricity

“Never underestimate the bandwidth of a person driving a van full of magnetic tape.”

This is what one of Mike Hazas’s college professors told him years ago; a kind of digital Zen koan that points out how tortuous the path is towards optimum sustainability.

Hazas is a lecturer at Lancaster University’s Computing and Communications department. After getting an electrical engineering degree in the US, he won a fellowship from the National Science Foundation and went to Cambridge University to earn a PhD in mobile computing. Once at Lancaster, he added a degree in sociology into the mix, and became interested in how technology affects human life and the impact of energy on climate change.

“It’s always worth asking ourselves if digital really is a more sustainable way of going forward or are we leading ourselves into a trap,” Hazas queries. “With the new technology comes new challenges.”

We watch things in more places at more times and on more screens than ever before. Yet we turn the lights out before leaving a room to try and save electricity, when the energy our 24/7 digital connectivity consumes is skyrocketing.

Is digital really a more sustainable way of going forward or are we leading ourselves into a trap?

Connectivity itself has altered our behaviour in how we consume video. Research has measured the traditional viewing spike that happens around prime time, but now there is a second much bigger peak at night as people head to bed. When Netflix CEO Reed Hastings said his company’s biggest competitor was sleep, he meant it.

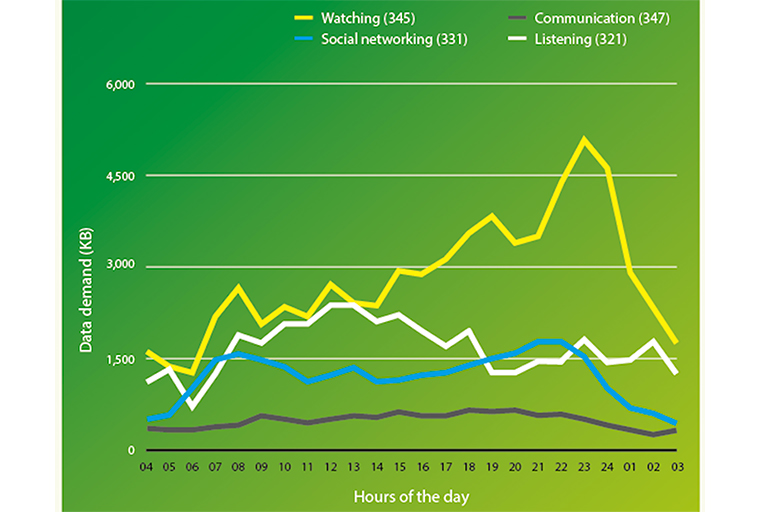

This graph, from a 2017 Lancaster University study, shows traffic aggregates for different categories like video streaming and social networking. It is drawn from a data sample of 398 Android devices in the UK and Ireland. There are two visible peaks in the ‘watching’ category (video streaming): one at traditional prime time and another later on as people head to bed and take their phones and tablets with them (this ‘bedtime peak’ was also confirmed in subsequent studies run by the university).

The graph above redrawn from fig. 5b in “Demand Around The Clock: Time Use and Data Demand of Mobile Devices in Everyday Life. In proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems” by Kelly Widdicks, Oliver Bates, Mike Hazas, Adrian Friday, and Alastair R. Beresford

Our instincts may tell us that something as weightless and invisible as video data could hardly be a major energy consumer, but the amount of energy required by the digital content world is big – and growing.

“If you count everything – consumer devices, computers in offices, all the networks, as well as the data centres – you’re looking at 10% of global electricity use,” says Hazas. “Of that, about 3% of global energy use goes to video streaming.”

Those numbers may be surprising, but the more unnerving statistic is the rate video consumption is growing. Presently, Hazas puts the rate of growth in video at 34% per year. Moreover, the rate of mobile traffic is growing at 50% per year.

When computing what the power consumption of video will be in the next decade, it’s important to note that much of the world has yet to be adequately connected digitally. The streaming revolution has just started to reach sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Asia and South America. Mobile is likely to be the way forward for these populations,

with 4G and 5G networks making it easy to boost the numbers of mobile subscribers in these regions at scale.

The really dismaying thing is that mobile actually uses more energy than terrestrial-based networks.

“If you can stream over a broadband or fibre network, that’s actually better. If you’re streaming over 4G, you consume roughly two and a half to three times more energy in total,” explains Hazas.

The arrival of 5G is not likely to solve the energy consumption problem. It’s expected that, although 5G is more efficient, the widespread adoption of 5G and the new content opportunities it brings, will render any energy savings through efficiency irrelevant.

The energy consumed by digital video is also going to be multiplied by bigger, better and brighter video formats, and the devices they are viewed on. A 4K TV set – by virtue of its size if nothing else – is going to be a bigger power hog than an HDTV, but when we get to HDR, power consumption increases noticeably, since quality HDR TV’s must be substantially brighter than even 4K screens.

“Watching on a mobile phone, 90% of the viewing session’s energy spent in distribution, is in the cloud. Whereas, when watching something on an HD projector or 4K TV, most of that energy is spent at the consumer device. That trade off is an important thing to keep an eye on,” Hazas warns.

About 3% of global energy use just goes to video streaming

How green is my platform?

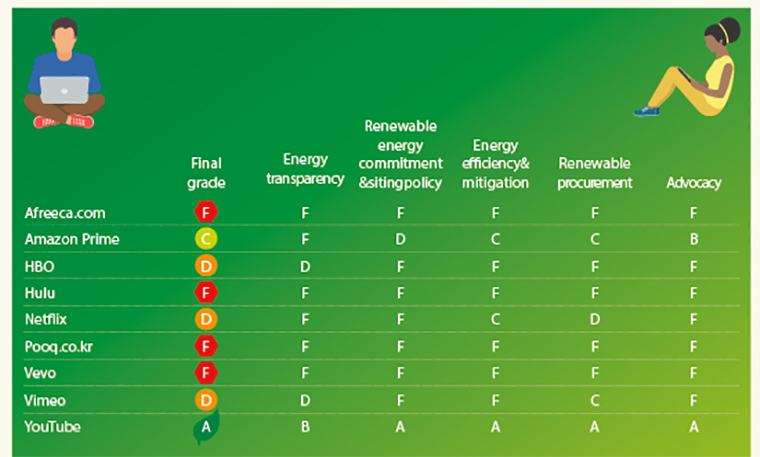

In 2017, Greenpeace published its Clicking Clean report, which looked at the energy consumption of digital companies and their levels of commitment to sustainable practices. Apple and Google continued to lead the sector in their use of renewable energy, as well as using their influence to encourage governments and partners to adopt sustainable practices.

Clicking Clean included a “report card” for companies operating in different sectors, including CDNs, video streaming, music streaming, social media, blogs, search engines, messaging and ecommerce. Each company was given an A to F ranking in five areas: energy transparency, renewable energy commitment & siting policy, energy efficiency & mitigation, renewable procurement and advocacy.Above are the report’s ratings for streaming video platforms. Read the report here: FEEDClickClean

According to Hazas, a good rule of thumb is that, roughly speaking, a standard LED-based HD television consumes about the same amount of power in displaying video as was consumed by the network and data centres in streaming it there.

Beyond the device a video is viewed on, resolution itself has an energy cost.

“If you look at what Netflix calls Super HD compared to rates typical of YouTube, you’re looking at three, four or five times the energy consumption at the fastest rates,” explains Hazas. “And with 4K, it will be two to three times more. And then you can imagine, if you’re watching an 8K stream, in 15 years’ time, you’ll be consuming quite a lot of energy and that’s just in the streaming.”

The flexibility of tools in the digital realm means that new businesses or services can be spun up very rapidly, and can scale enormously in a short period of time. This means a potential for rapid – global – growth, and the power consumption that goes with it.

What do we do?

So how do we in the streaming industry reduce our power consumption? Hazas believes that changing your travel habits is still one of the sure-fire ways to do this, but calculating energy consumption isn’t always straightforward.

Cool tools: The climate in Lulea, Sweden allows Facebook to use outside air to cool its tens of thousands of servers on campus

“Teleconferencing is a clear win. It’s better than flying or even taking the train. It’s even better than your taxi journey to the train station. But in other areas, it’s less clear,” he says.

Hazas notes the research done in the ‘life-cycle assessment’ field, which studies the environmental impacts of a product through every stage of its existence, from extraction of raw materials to manufacture and distribution to disposal. “One paper a few years ago looked at the distribution of large triple-A classified video games through Blu-ray disc versus digital distribution over the internet. They found that, for large games, it was actually better to distribute on Blu-ray. Of course, that comes with a caveat: you may be downloading almost the entire game again every time you get a new update. But for the initial distribution, there are arguments for more traditional media,” he explains.

Some of the digital giants responsible for a good chunk of online video activity have been aggressive in powering their servers using entirely renewable energy. So if the big platforms are switching to renewable energy anyway, is there even a problem?

Well, we all know people tend to run into trouble when they assume there’s an unlimited amount of any resource – even if that resource is sunlight and heat from inside the planet.

Hazas believes that provisioning renewable and green power should go hand in hand with a company wanting to build a big infrastructure project.

One paper found that, for large video games it was better to distribute on Blu-ray

“It comes down to a policy question for governments. The way I think about it is if they’re going to build a data centre, they should provision a renewable energy source at the same time as a new development that might not have otherwise happened, it starts to make things even. It’s a good way to go forward,” says Hazas. “But what usually happens is the company might make some green provision, but then during peak times might buy back excess power from the national grid, which during the cold winter months essentially requires coal-fired power plants to be spun up.”

Hazas points out that it’s also better in the long term for these big platforms to build their own green infrastructure, because it will be eventually less expensive than the alternatives.

“Companies need to have an awareness of the energy and environmental costs of their service, and then make consumers aware that this is something they keep in mind when deploying services,” notes Hazas. “In addition to saying ‘we’re a green company, we’re keeping an eye on how much energy we consume and where it comes from when we deploy video’, you could have different versions of a video available, which would display the environmental impact according to different resolutions or length. It’s something that could boost a company’s image, especially if online video continues to grow as quickly as it has been.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of FEED magazine