Spatial audio explained: Sound and vision

It promises a personalised, ambient sound-space in perfect sync with visual storytelling. But just how does this still-experimental audio tech work?

Spatial audio explained: It promises a personalised, ambient sound-space in perfect sync with visual storytelling. But just how does this still-experimental audio tech work?

Even with a visual medium, audio can make or break the experience; when done well, audio provides indespensable enrichment for viewers. But getting the audio right, especially using the complex layers of new, spatial ‘sounds beyond stereo’, can be a mountain to climb.

Luckily, the growing demand for immersive interactivity in video formats – across all screen shapes and sizes – has opened a path for exploring new ways of integrating innovative, spatial audio in sound and vision. Amongst industry peers, academics and R&D circles, this clever format is still in its ‘wild west’ phase, with creators and consumers experimenting with new tools and techniques in spatial production, to enhance and augment our video experiences with full, glorious, 360° surround sounds.

Spatial audio now goes way beyond the VR headset and is almost, dare we say, entering the mainstream, mostly thanks to the rising popularity of Location Based Entertainment (LBE) in shopping malls, branded experiential and theme parks. Add in mobile-led, audio-enhanced augmented reality (AR) layers on social and retail platforms, and it looks like spatial audio has a bright future.

A PWC report, Seeing is Believing, released in December 2019, predicts that “VR and AR has the potential to add £1.5 trillion to the global economy by the year 2030”. That’s a whole decade ahead of us for pumping up the spatial audio volume.

The next step

Before exploring some more of this visual potential, let’s describe what spatial audio is, without going too deep down the rabbit hole of 3D sound vs 360° sound (vs surround sound vs Auro-3D, vs Dolby Atmos vs binaural, vs immersive audio…).

In a nutshell, spatial audio – also known as ambisonics – is the cooler big sister of the 360° surround sound that most of us are familiar with. It comprises lots of strategically placed speakers in cinemas, and soundbars or cross-talk cancellation stereo speakers in the home or office. It does what it says on the tin by literally surrounding the space we occupy with sound, as we remain in static wonder.

Bose frames implement spatially programmed sound mixes

But with an intelligently produced spatial experience, the listener takes the sound with them – all around them. It’s a personalised, three-dimensional atmosphere enhanced by precision location tracking and superior audio immersion – and hopefully, some good storytelling. As you move around, the audio shifts with your movements, organically imitating how you listen to things around you in real life.

Sometimes, spatial audio can guide and lead the entire experience, especially if enhanced by bleeding-edge wearables like Bose Frames, which utilise noise-cancelling tech and implement spatially programmed sound mixes. This kind of kit can enable developers and experience designers to create a true 360° soundscape transferable to a real-world setting, possibly surrounded by virtual actors or video, or our imaginations.

To go a step further, clever use of spatial audio within multi-platform, real-time video experiences can dramatically enhance cinematic video elements – perhaps using headphones that are enabled with both head-locked audio and head-tracking – to create an awesomely rich experience for the viewer.

isual potential, let’s describe what spatial audio is, without going too deep down the rabbit hole of 3D sound vs 360° sound (vs surround sound vs Auro-3D, vs Dolby Atmos vs binaural, vs immersive audio…).

In a nutshell, spatial audio – also known as ambisonics – is the cooler big sister of the 360° surround sound that most of us are familiar with. It comprises lots of strategically placed speakers in cinemas, and soundbars or cross-talk cancellation stereo speakers in the home or office. It does what it says on the tin by literally surrounding the space we occupy with sound, as we remain in static wonder.

But with an intelligently produced spatial experience, the listener takes the sound with them – all around them. It’s a personalised, three-dimensional atmosphere enhanced by precision location tracking and superior audio immersion – and hopefully, some good storytelling. As you move around, the audio shifts with your movements, organically imitating how you listen to things around you in real life.

Sometimes, spatial audio can guide and lead the entire experience, especially if enhanced by bleeding-edge wearables like Bose Frames, which utilise noise-cancelling tech and implement spatially programmed sound mixes. This kind of kit can enable developers and experience designers to create a true 360° soundscape transferable to a real-world setting, possibly surrounded by virtual actors or video, or our imaginations.

To go a step further, clever use of spatial audio within multi-platform, real-time video experiences can dramatically enhance cinematic video elements – perhaps using headphones that are enabled with both head-locked audio and head-tracking – to create an awesomely rich experience for the viewer.

Help for humans: The scope for spatial audio goes beyond entertainment, and could have health and well-being application

Cinema leads the pack

Mirek Stiles is head of audio products at Abbey Road Studios, and founder of the Abbey Road Spatial Audio Forum. This is an industry group that aims to help artists deliver the best possible spatial experience via practical experiments and academic projects. Stiles – a passionate and supportive advocate of the format – is appreciative of the fact the moving picture industry has always pioneered adoption of spatial audio formats.

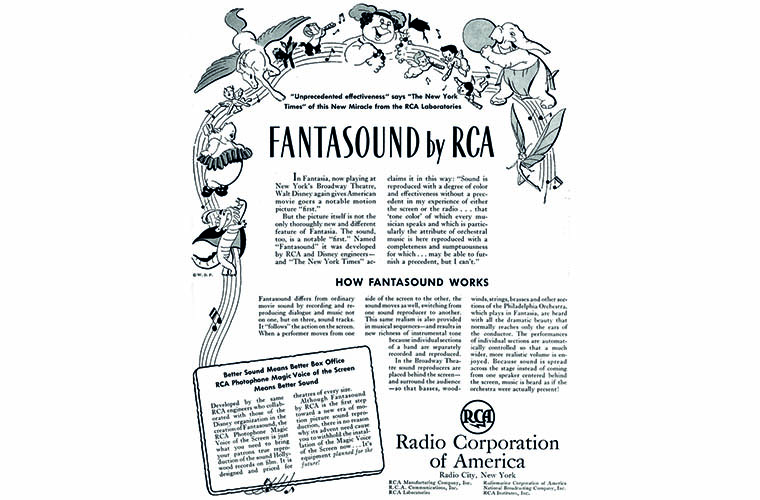

“Cinema is and always has been the leader in providing the consumer with spatial audio, even dating back to the 1930s with early surround playback systems like Fantasound,” Stiles explains, referring to the pioneering system employed for Disney’s Fantasia. “Today, Dolby Atmos is the immersive experience to be found in the cinema. Directors are still discovering and experimenting with how it can be used to enhance the story on screen. There are also a lot of music-only Atmos mixes that provide a huge sound stage, and many of these are currently available to the consumer via services such as Amazon Music.”

Alongside industry experts, academics specialising in audio R&D and best practice understand that what we’ve learned from the big screen can translate into learnings for small-screen experiences, too.

“Ever since the days of Disney’s Fantasound, we have seen constant developments in the use of spatial audio in the cinema, the most significant being the 5.1 surround sound format and its derivatives that emerged in the latter quarter of the 20th century,” says Dr Gavin Kearney, associate professor in audio and music technology at the University of York, and also a member of Abbey Road Spatial Audio Forum.

“However, there is now the potential for everyone with mobile technology to experience immersive audio through the use of binaural sound, which has been well utilised in the recent VR explosion,” Kearney adds.

Mirek Stiles also enthusiastically endorses the use of spatial audio in a VR context. “I love ‘six degrees of freedom’ experiences where I can walk around a performance in a room as it’s being played, and the audio is head-tracked to where I am facing and what I am looking at. I hope we see and hear a lot more content over the coming years that takes full advantage of six degrees of freedom sounds, in both VR and AR.”

Outside of the engineering think tanks, a great example of spatial audio integrated with 360 VR video is the fantastic Snowball, created by Studio Geppetto back in 2016 (that’s some time ago in VR terms). Still available to view (and hear) on YouTube, the story combines simple graphics of a woodcutter going about his day, only to find a giant pair of eyeballs staring down on him, which pull back in Russian doll-style story layers to reveal he’s actually inside a snow globe.

The playful sound bed composition that twinkles in the background was programmed entirely as a spatial audio experience using interactive software, by French audio developer Noise Makers. The effect creates a magical sensation of being inside the snow globe, hanging out with the lumberjack and woodland animals. All in all, it’s perfection, and one of the best examples when industry peers ask for best-use cases for creating spatial audio layers with their visuals.

Tools of the trade

The earlier days of spatial audio production relied on simple microphones and hours (and hours) of manual design. We’re now in an era with more software and tools available than ever before. This has enabled more creators, industry peers and academics to test the waters in early stages. The industry has taken note, too, with more brands, broadcasters and even film festivals the world over showing off some fantastic spatially boosted video, even dedicating specific awards to sound experiencesTools and kits have also come a long way, such as Microsoft’s surround-sound emulator Windows Sonic, plus advances from Sony, Magic Leap, and Google VR’s SDK engine. This last piece of tech is optimised for mobile VR, and guides the human ear to experience localised sounds coming from multiple levels, frequencies and directions.

Facebook and YouTube have also created free, user-friendly tools which, boosted by social media, should help spatial audio reach a mass audience. Kearney agrees that these social giants supporting the format “opens up exciting possibilities into realistic, or hyperreal, meeting spaces and experiences.”

Imagine being able to watch a Led Zeppelin concert in Japan, in 1971

For the more advanced, engineering software such as Mach1 (a new partner to Bose’s spatial platforms) and G’Audio Lab’s Works plug-in are both brilliant examples of sophisticated tools available to all. Blue Ripple is another 3D sound software tool that gets a special shout-out from Stiles:

“They are developing exceptionally good sound software for both the traditional music creator and game/VR developers, providing a complete workflow from mixing in the DAW to spatialising sound in game engines like Unity.” If you are recording your own audio from scratch, remember to pick up a good mic from a company like Core Sound, who, as recommended by Stiles, “have some very cost effective ambisonic models – an encouraging push in the right direction to create better sounds all around.”

Into the future

With 2030 looking like a reasonable goal for the full integration of spatial audio into all visual content, the dreams for its impact on content are big.

“I would like to see a mixture of gaming, film, VR/AR and AI techniques used to allow people to experience times in musical history in ways previously impossible,” muses Stiles. “Imagine being able to watch a Led Zeppelin concert in Japan in 1971, or sit in Studio Two, Abbey Road, as The Beatle track A Day in the Life is recorded – or experience Mozart perform in Vienna, 1784. We are currently experiencing technology from various disciplines merging together in ways that would have been unimaginable ten years ago. I think we are going to be having some mind-blowing musical experiences.”

On the academic side, Dr Kearney leans toward the cosier option.

“It would be wonderful to experience a completely realistic virtual environment, with spatial audio, from the comfort of your living room. Whilst this can be achieved to some degree with existing VR technologies, we are still a long way from full, holodeck-style experiences.

“However, there’s so much we can already achieve with spatial audio that only scratches the surface. It will not only continue to benefit immersive experiences in music, gaming, VR, cinema and TV, but will have profound implications outside the entertainment industry as well, such as in teleconferencing, training, education, mental health and well-being.”

With new software plug-ins, new hardware, new creative design that offers viewers reactive, real-time responsiveness, and with the continued support of existing and new social media tools, there are more opportunities than ever to create sounds in 360°, and place spatialisation within all video environments.

This article first appeared in the February 2020 issue of FEED magazine