AI moderators | Taking content to the cleaners

Posted on Dec 11, 2019 by Alex Fice

Content moderation jobs are awful. But are AI moderators the solution to the internet’s trash problem?

According to The Wall Street Journal, “the equivalent of 65 years of video are [sic] uploaded to YouTube each day” and humans are still the first line of defence against protecting its 1.9 billion users from exposing society’s darkest impulses.

But resolve to remove humans from the ugly business of content moderation grows as more and more horror stories unfold from former employees, and as the cost of employment increases. Companies are loath to devote anything more than the bare minimum to a task that does not contribute to profit. One man, who asked to remain anonymous, told BBC reporter Jim Taylor in 2018 that he had become so desensitised to pornography after reviewing pornographic footage all day that he “could no longer see a human body as anything other than a possible terms of service violation.” But his colleagues had it worse: “They regularly had to review videos involving the sexual exploitation of children.”

The negative effects of human content moderation aren’t just being felt by those in the job role; brands are also starting to suffer. Due to public opinion and regulatory pressure, there are increased risks of penalties involved for monetising content in the wrong context.

Actions are much more difficult to classify than objects. For example, kissing is an action, but nudity is an object

“Humans cannot simply keep up with managing, versioning and curating content for the fast-paced world of modern video,” says Mika Rautiainen, CEO of Valossa, a Finnish company providing AI tools for assessing video content at scale.

“Advertisers are more conscious of the content they advertise with, and online video platforms are in need of deep metadata to help identify elements that make the content hit the right audience, in order to go viral,” says Rautiainen. “Today, virtually anyone has access to dangerous online content and wrongly placed video advertisements could cause negative publicity for advertisers.”

Brands need to be able to identify content and profile it based on its potential to cause offense to effectively contain the distribution for the right audiences. Brands also need to be reassured that their content is going to be moderated properly amongst the surge of other content generated online today.

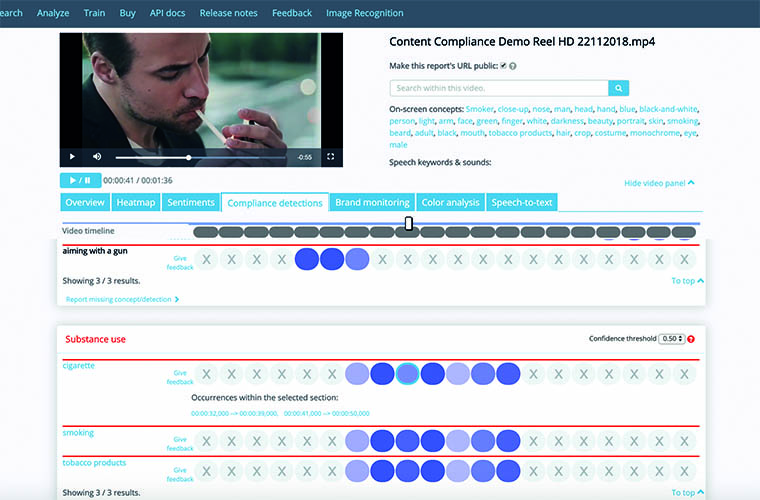

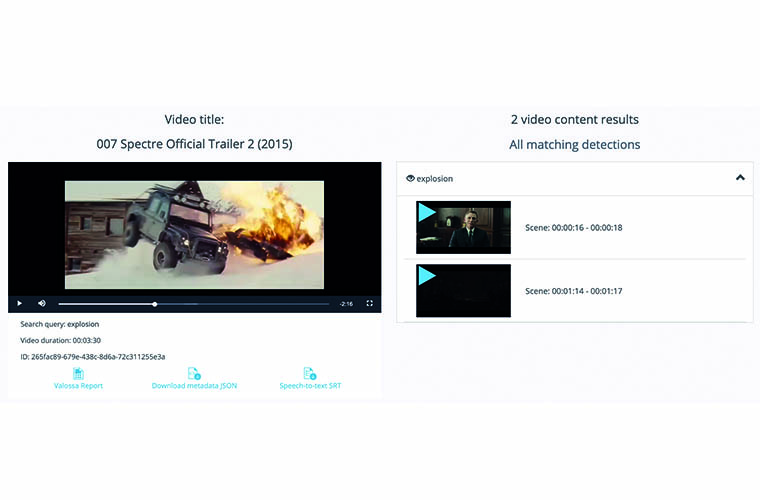

Recruit the robots

Valossa’s solution: a state-of-the-art AI and machine learning technology with computer vision and pattern recognition. The tool is capable of handling huge amounts of content uploaded and distributed across multiple platforms, and can automatically describe and tag what appears on screen, as well as the context in which it appears.

Rautiainen explains: “For example, a person on the street with a knife in hand is different from a chef who is using a knife to chop vegetables; the actions are different, though the identified knife concept is the same. With this combined metadata, the tool creates an emotional intelligence that can identify sentiments from human facial expressions. Facial expressions are used to evaluate negative or positive human sentiment in a scene.”

The AI moderators identify a huge variety of nuanced concepts around sexual behaviour, nudity, violence and impact of violence, substance use, disasters and bad language, including sensual material like partial or occluded nudity, cleavage, lingerie, manbulges, suggestive content, smoking, alcohol – you name it. The broad vocabulary for inappropriate content elements also means that the engine can be customised for different regional preferences.

Interra Systems, which specialises in systems for video quality control, is also working towards simplifying the toil of content moderation. The company provides software for classifying audio-visual concepts, and uses AI and machine learning technologies to identify key elements in content according to the regulations of different countries, regions or organisations.

“The basic algorithm inside the software is focussed on identifying concepts, then there are filters outside of that which will try to map out which audience and geography the content is appropriate for. These filters can be adjusted and revised because the software is constantly learning,” says Shailesh Kumar, Interra Systems’ associate director of engineering.

Schooling

AI-driven content moderation tools require a substantial amount of sample data in order to identify and analyse objects, actions, and emotions that determine the potential impact of a piece of content.

“We have a full data team that acquires and prepares data for the AI, and we have advanced machine learning engineers that monitor the learning process and make sure that the appropriate context is being learned,” says Valossa’s Rautiainen.

Kumar explains that it’s important to look out for what he refers to as “false positives”. False positives are cases where the AI learns a concept or an action that is not there.

“We take our data set and we run our software on it to identify any false positives or false negatives (where concepts are there). Then we try to figure out what is missing in our training or design of the classification model and go through the process of training and measuring the results again.”

Some video concepts are harder to train than others. The complexity depends on the variations in concept representation. “Making cognitive AI infer threatening situations from visual media scenes is more challenging than recognising weapons in view,” says Rautiainen. “The AI technology is getting better every month, though, so its inference capabilities are gradually increasing with the challenging concepts.”

“Actions are much more difficult to classify than objects” explains Kumar. “For example, kissing is an action, but nudity is an object. Action cognition requires using two-dimensional and three-dimensional convolutional neural networks (CNN) to track an action over multiple frames, which helps classify whether an action is happening.”

Video use cases are also different from the typical AI challenges of data classification, because the forms and patterns of information in video content do not have any predetermined representation constraints, so machine learning models need to perform well with any kind of inbound data. This unfettered content concept is referred to as ‘in the wild’, and in the wild, models are tasked with minimising false or missing interpretations without knowing the extent of variety in content patterns.

Rautiainen explains, “if you train a domain-constrained classifier, for example one that sorts out pictures containing only cats or dogs, it becomes easier to reach high classification accuracy. However, these domain specific models would not survive ‘in the wild’ recognition tasks, since they would see cats or dogs in every data sample they inspect. This is because that’s all they have ever learnt to see.”

What happens to the humans?

Most believe that AI isn’t nuanced enough to take over human content moderation. In 2018, Forbes reporter Kalev Leetaru wrote, “we still need humans to vet decisions around censorship because of the context content appears in.” This has been true in the past; remember the Facebook censorship fiasco where its algorithms removed the iconic Pulitzer-winning photograph of the Vietnam war?

This is a grey area; the struggle between free speech and censorship will still require some human judgement

The photograph depicts a group of children, one of whom is nude, running away after an American napalm attack. It was posted by a Norwegian writer who said that the image had “changed the course of war”, but Facebook removed the post because it violated its terms and conditions against nudity.

This is a grey area AI technology is still trying to get a grasp on; the struggle between free speech and censorship will still require some human judgement. But governments are taking more regulatory action and publishers are being forced to react. It may be just a matter of time before content moderation is fully automated.

“We disagree with the claims that technology to automatically detect and flag and potentially inappropriate and harmful content does not exist – it does, and publishers are beginning to adopt it,” says Valossa’s Rautiainen.

Perhaps it’s no longer an issue of whether AI can replace humans to scrub the digital sphere of excrement, but an issue of whether our free speech will be overseen by robots online.

This article first appeared in the May 2019 issue of FEED magazine.

AI and machine learning archives