Worlds 2020: The legend grows

The pandemic meant the League of Legends World Championships went virtual. In this case, virtual meant bigger and better

The pandemic meant the League of Legends World Championships went virtual. In this case, virtual meant bigger and better

Words by Ann-Marie Corvin

The League of Legends World Championship, affectionately known as ‘Worlds’, is probably the biggest fixture on the esports calendar, broadcast globally in more than 19 languages.

In a regular Worlds year, audiences are treated to the grandeur of a multi-city show, attended by thousands of hardcore fans who are as much a part of the spectacle as the competition itself.

The show has around 40 distribution outlets, including Twitch, YouTube, and Facebook in the west, but others include cable networks in South America and Korea, as well as the Chinese video-sharing website Bilibili.

The 2019 tournament pulled in almost 100m concurrent viewers at its peak, with an opening ceremony beginning the final that has become a technical showcase for organiser and League of Legends publisher Riot Games (see boxout).

The coronavirus pandemic meant that Riot had to reconfigure the tournament and rethink its production methods.

Worlds 2020 took place in just two buildings: a fan-free Shanghai Media Tech Studio and the city’s Pudong stadium hosting the finals that housed a live audience of around 6,000 socially distanced fans (a vast reduction compared to the usual crowd of 15,000).

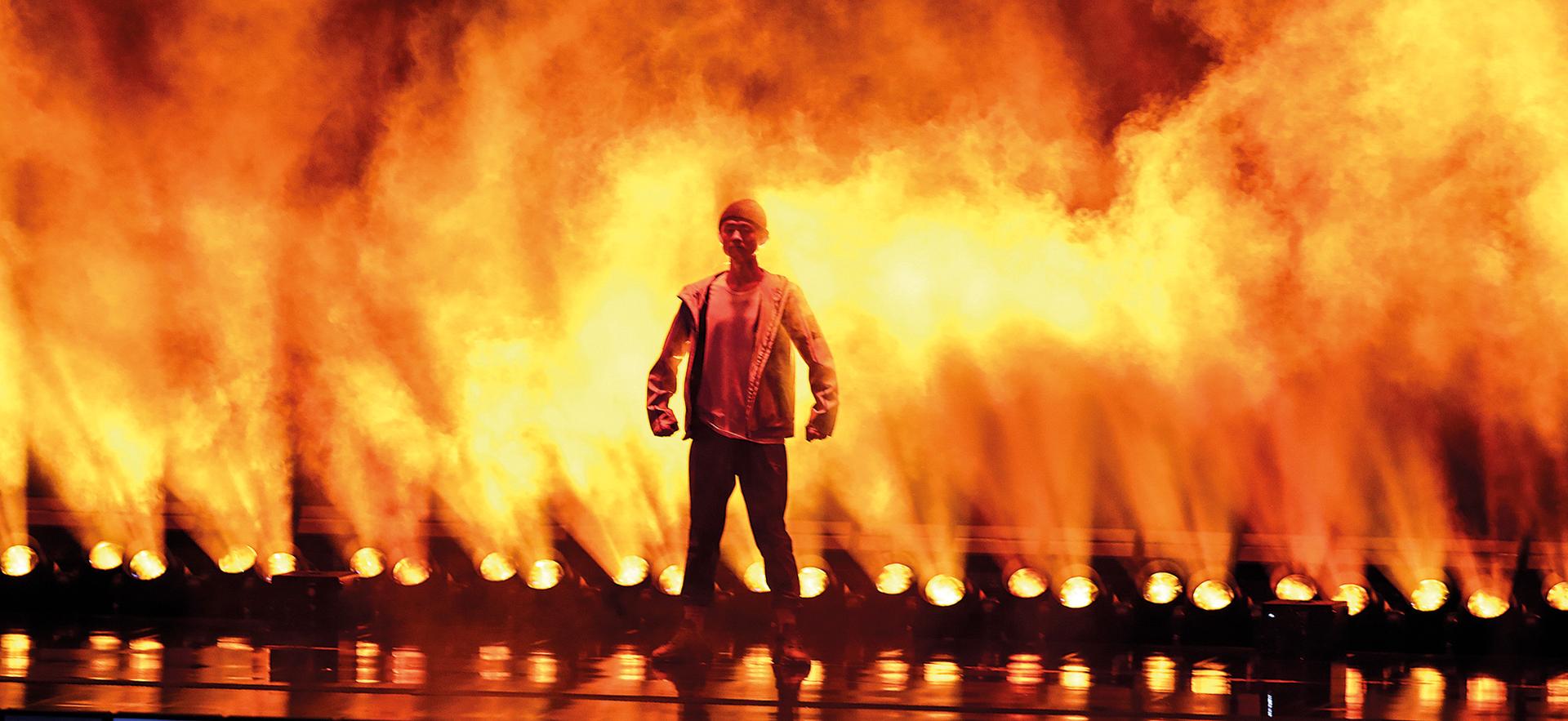

While the event was reduced in scope, it did not disappoint, thanks to stunning extended reality sets. Behind the scenes, Riot added further to its already well-virtualised production model, so staff based globally worked from the safety of their own homes.

FEED spoke to the esports tech lead at Riot Games, Scott Adametz. His nine-strong team, based in LA, is responsible for the backend infrastructure, which supports big events like Worlds.

“Technically this show is the most ambitious that we’ve ever done,” says Adametz.

“In the middle of a pandemic, when we probably should have been downsizing, we thought bigger about how we could make the show better, despite limitations.”

These ambitions were visually apparent in the virtual sets. Riot’s team used extended reality to merge physical and virtual worlds, hosting early stage matches against the backdrop of a cyberpunk Shanghai skyline, or amid a flooded landscape.

One company responsible for the sets was Super Bowl half-time show regulars, Possible Productions. “Those guys really understand spectacle,” says Adametz. The other was Lux Machina, the in-camera and virtual production display company behind The Mandalorian’s sci-fi landscapes.

More than 900 LED tiles were used for the sets in total, displaying visuals at 32K resolution and 60fps. These visuals were rendered using a modified version of Unreal’s gaming engine.

Rather than sticking to a single point of view of the virtual environments around the players, there were two perspectives running simultaneously all the time, enabling the broadcast team – using a four-camera shoot – to swap between different points of view and have the background environments stay coherent. According to Adametz, Worlds is one of the first productions to attempt to do this in a live broadcast environment. The biggest challenge this presents is timing and sync.

“It’s easy to achieve in post, but we did this live with four simultaneous cameras. That’s another area where we had to take the next leap. How can you have an LED wall and a virtual extension stay in sync and not switch between cameras, while still seeing the view and perspective of the last camera?”

According to Wyatt Bartel, Lux Machina’s senior technical director, code developed by the teams at Riot, Possible and Lux MC provided a solution to this problem.

“The code allows game data to pass back and forth between the Lux MC-modified Unreal Engine. Moments like Champion Select, player deaths and Baron trigger the stage to begin our special effects, making the digital world flow into the real world dynamically,” he explains. “I don’t think any team has done as deep an integration between technologies as the Riot production team did at Worlds 2020.”

Decentralised collaboration

According to Adametz, Riot usually has more than 1300 staff producing events as big as Worlds.

“The same number were working this year – the majority safely in their homes, like me,” he says.

The Worlds has been broadcast remotely with, it maintains, no loss of quality, since 2017 – eschewing broadcast production trucks in favour of a remote model to produce and distribute the Worlds.

“We were running into limitations of what an OB van can provide, especially factoring in next-gen tech like real-time rendering and the 32K resolution backdrops used for the stages – it’s a lot of kit and prep,” explains Adametz.

The remote model distributes a cleaned-up feed to regional production teams that use the backbone of Riot’s network to produce the show.

“A world feed comes from the host country, which is improved and localized. We add different graphics, languages, roll outs and features,” he explains.

Riot has 11 regional teams as well as another five or six third-party production partners. Usually, regional studios require a level of on-site access to the feeds from a video village near the venue, which is usually connected via a local SDI. The pandemic meant that local partners worked remotely and received these feeds via IP.

“On a typical show, we have more than 100 individual feeds that are moving around the venue. This year, we had to do the same number of feeds, but to people’s homes and spread all over the world.”

To ensure all production partners had the same capacity, and were equipped with the same resources to do their jobs, Riot’s North American operation collaborated with its Oceanic branch on a solution – their own internal streamer application.

“We essentially had to build our own internal content delivery network that gives people the functionality to pick any source, any camera, and watch it from the safety of their home,” says Adametz. “We called it the Worlds Streamer – it’s a web-based interface that allows you to see all the feeds and enables you to select a multi-view that suits you,” he adds.

Local partners decide what they need and the streamer uses the open source streaming protocol SRT to achieve a reliable but secure transport.

“This means that if there’s any packet loss it can repair. If you’re running out of bandwidth on your home internet, you can downsize the number of views you pick until you find the amount that gives you what you need – but never any more as this would saturate your bandwidth,” Adametz explains.

Nimble workflows

At the centre of Riot’s virtual production system are two virtual video switchers running in Amazon Cloud. The primary switcher is for recording, host cams, observer feeds and graphics; the second handles audio, record and playout, including the master audio mix, video packages and recording. All this can be spun up to the cloud in a few clicks.

The outputs are sent to Nimble Streamer, a software media server running in the cloud that handles the distribution to viewers (via its distribution partners). The program feeds to referees and shoutcasters and the multi-view feeds to the production crew.

“Nimble has been one of the big pluses from all this,” says Adametz. “It’s a streaming software that takes streams in and distributes them across the globe. We’ve used it before, but this year it’s the reason the show could be done remotely,” he says.

According to Adametz, another ‘big win’ for the production was the introduction of JPEG XS video codecs into the 2019 Worlds tournament.

“We were the first to try JPEG XS, a new way to move video and audio that leads to lower latency and higher quality production. We’ve now standardised this as part of the production.”

To eliminate latency for the players themselves, Riot ships over gaming servers to the venue, under close watch by security guards. This year, the servers resided in a data centre in Shanghai near the facility, as bringing the servers on-site was not possible. “So, that’s near zero latency, but not zero,” he says. These gaming servers are also used to automatically generate live statistics – a key component of the experience for esports fans.

“We take those stats at a very high granularity and put it into a stats pipeline in the cloud that distributes it to stats partners all around the world. Then, we can trigger things like awesome overlays. As a fan, you can see these live stats constantly updating via the video window.”

Adametz adds that Riot’s digital team has been working directly with Twitch and YouTube on several fan integrations that reward the viewers who would otherwise have been cheering in stadiums.

“We had worked very hard to enable drops [rewards you can gather as you watch]. More than 100,000 fans received these drops. Fans could insert their own messages and there was also a cheering section – that produced real engagement, even when you weren’t able to be in the stands holding up a sign to support your team.”

According to Adametz, Riot’s approach to building its infrastructure has changed due to the pandemic.

“We’ve already pivoted a lot of our plans for projects within our five-year road map because of Covid. We can’t take for granted that we will be able to work together in a single room,” he says.

“We have to think more virtually. Riot’s never been hardware-first, but certainly not now. Once you go digital, it’s very difficult to undo that. Going forward, we’re looking at software solutions, things that can be virtualised or run in public cloud.”

And for those who don’t already know, South Korea’s Damwon Gaming took the Worlds 2020 title, beating Suning Gaming of China in the final.

This article first featured in the Winter 2020/21 issue of FEED magazine.